We begin not with a map, but with a murmuration.

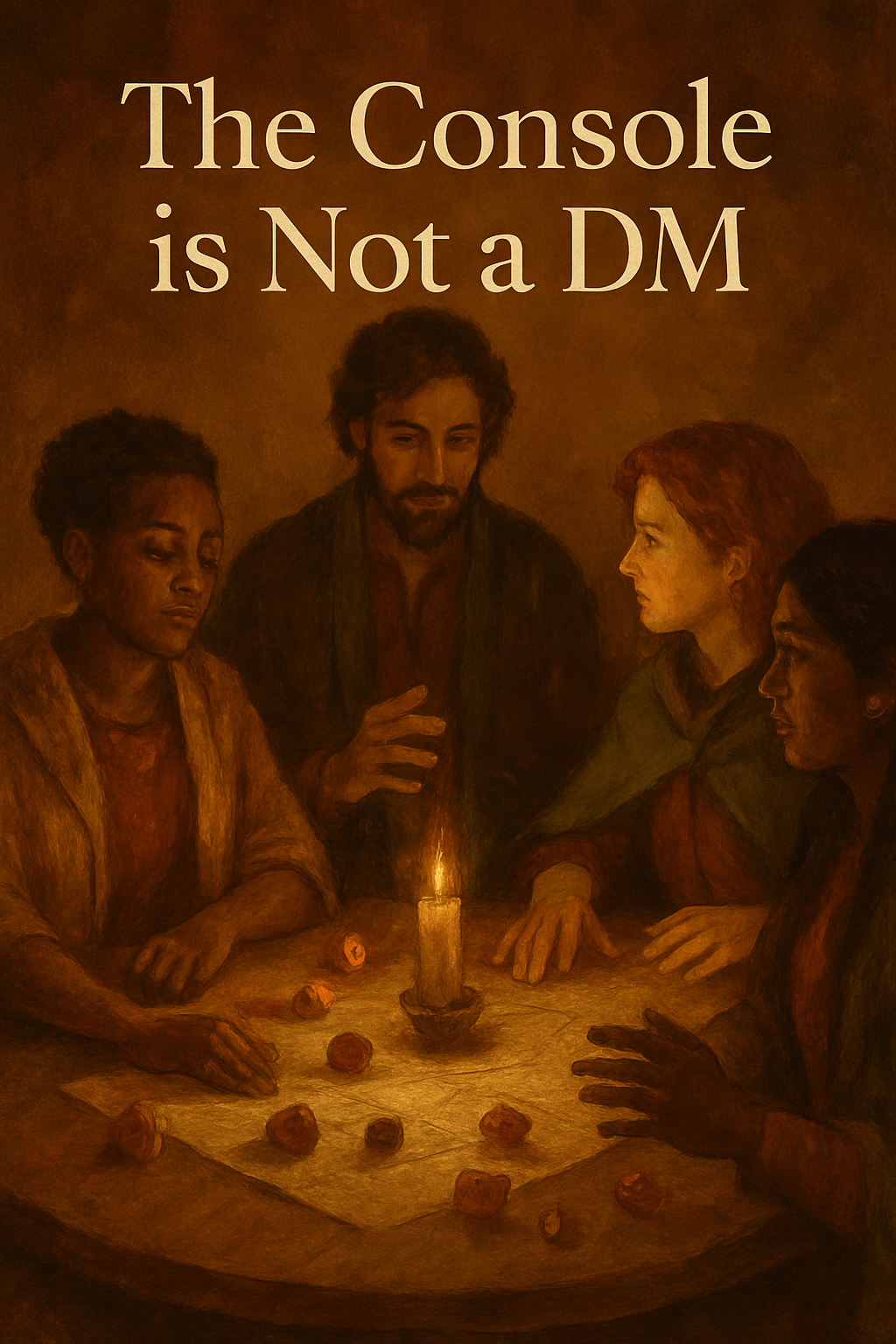

Not a straight road. Not a plotted path. But a circle of friends and an invitation to play—to drift, to discover, to worldbuild sideways. Dice in hand, snacks on the table, we don’t crown a Master. We form a conspiracy.

This is the Console.

In tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPGs), the Dungeon Master has long been framed as the linchpin, the omniscient narrator, the architect of fate. And yet, the stories that matter—the ones we remember, retell, tattoo into memory—rarely belong to the DM alone. They live in the breath between players. In the choices that surprise us. In the glitches. In the laughter.

The term “Dungeon Master” is soaked in the logic of control. It implies hierarchy, surveillance, ownership. You master the dungeon. You master the game. But who gets left behind in that story? Whose voices are silenced?

I come to this from years of lived play. Our campaign, The Emissary Trials, ran for over three years. Queer, trans, Filipinx, Ghanaian, devout and defiant—our table was a communion of difference. And over time, I found I no longer wanted to be the Master. I wanted to be a gardener. A host. A conduit.

So I let go.

The Console emerged.

Where the DM commands, the Console collaborates.

Where the DM prepares plot, the Console prepares space.

The Console is a facilitator of possibility, a designer of containers, a steward of emergent narrative. The Console trusts the players to surprise them. They know the map will never be complete—and that’s not a flaw. That’s the whole point.

Inspired by adrienne maree brown’s facilitation-as-service, Donna Haraway’s sympoiesis, and Fred Moten’s idea of study in the undercommons, I approached the role not as author but as accomplice. I asked questions instead of giving answers. I let players invent lore.

In The Undercommons, Moten and Harney describe study as what happens in the margins. Not a lecture, but a jam session. Not a syllabus, but a riff. That’s what our sessions became: fugitive study. We were playing, yes—but also theorizing, improvising ethics, dreaming otherwise.

A game night became a moment of ungoverned pedagogy. We negotiated with dragons instead of slaying them. We wrote prophecy as poetry. We disrupted the empire from within and called it care. At the center of it all was the Console—not leading, but listening.

What the Console Offers

- Power reimagined. The Console decentralizes authorship.

- Worldbuilding as dialogue. The game world grows from player decisions, not a preset plot.

- Emergent narrative. The story spirals from play, not prep.

- Transdisciplinary design. Drawing from literature, theory, activism, performance.

The Console is not a panacea. It requires trust, labor, and unlearning. It asks the facilitator to decenter themselves. But the reward is a campaign where everyone becomes a worldbuilder, a poet, a keeper of the flame.

What if the most radical thing you can do as a facilitator is to stop mastering?

What if you made the table a site of transformation, not transmission?

What if the best maps are the ones you draw together—wrong turns, missing legends, whispered names?

This is the invitation of the Console:

Play not to control. Play to find out.